Kat’s 2021 Book List

As of Dec. 27, 2021 …

I did something different this year; I wrote a review of each book as I finished reading it instead of waiting till the end of the year. One result is some reviews that are longer than what I’ve written in the past. The lists (fiction and nonfiction respectively) are roughly in the order I read them except when I read more than one book by a given author, in which case, I grouped the author’s books together.

It’s not uncommon for me to binge on a particular author in a given year, and this year, it was Harlen Coben. I believe this was my first year to binge on a male author to the extent I did Coben; I’ve done smaller binges of Ken Follett and Robert Caro.

Sometimes I either set a reading theme for the year or a theme emerges organically. I didn’t think I had a theme going this year, but late-ish in the year, I realized I was reading a lot of true crime and had even read a book about the true-crime phenomenon. I read a fair amount of historical fiction. As usual, I read a few books about women of India/Indian-American women and women in slavery. I read 3 books about women in art, as well as a book each on art theft (and its prevention) and art forgery. I revisited a couple of what I call my pop-culture “comforting narratives,” The Beatles, Walt Disney, and Scientology exposes. I read what seemed like a lot of British stuff (set in England or British author), but an actual count shows only 10 books on the list. I did my usual dip into literary classics.

I often comment on the number of books I’ve read during the year; the goal is always 52. I reached that number in September and first published this list Sept. 25. It’s emblematic of my having had less on my plate this year than I have in a long time that I far surpassed that number. After publication, I set a new goal of 75 books, which I reached in late December, by far, the greatest number of books I’ve consumed since I started these lists (in 2010, I believe). At this writing, I am planning to add a 76th, albeit very short, book to my 2021 list.

I’m sure I’ve mentioned more than once that I tend to gravitate to women authors. I decided to see to what extent that’s actually true. In 2021, I’ve read 23 books by male authors and 52 by female authors, so more than twice as many by women but possibly fewer than usual, thanks in part to my Coben binge.

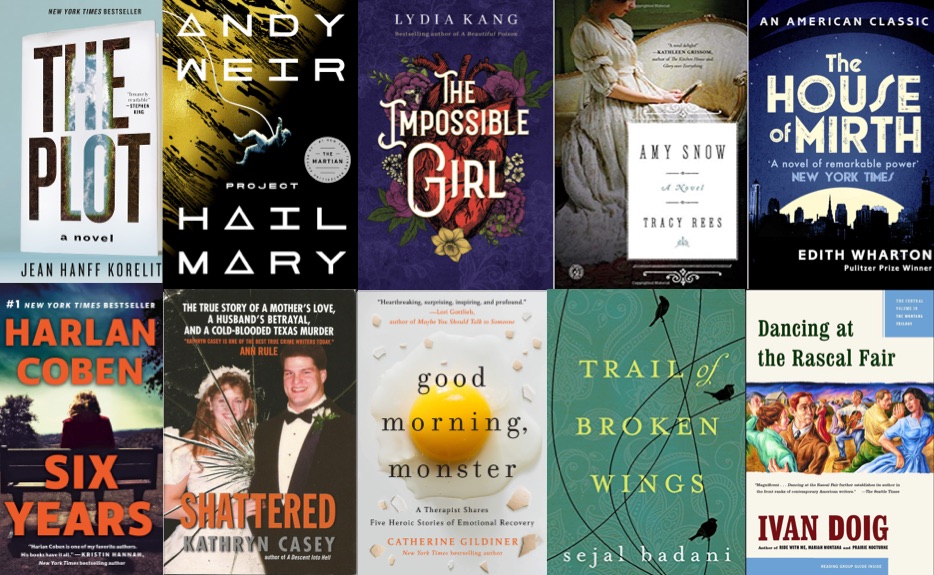

Favorites in Fiction (full reviews below)

- The Plot

- Project Hail Mary

- The Impossible Girl

- Amy Snow

Favorites in Nonfiction (full reviews below)

- Good Morning, Monster

- Shattered

- The Meaning of Mariah Carey

- The 1619 Project

A note to new readers of my annual list that I consume virtually all the books I read in audio form, thanks to my pathologically slow reading. Some of my reviews mention narrators of the audio versions.

Fiction

- The Overstory, by Richard Powers: I read this after several enthusiastic recommendations from friends, but I found it a bit of a tough read on audio. It reminded me a lot of Annie Proulx’s Barkskins, both novels being huge, sprawling, multi-character sagas with environmental themes. It was the sprawling, multi-character aspect that made The Overstory difficult on audio. I appreciated the many nods to storytelling, but I think I will need to revisit this one to really appreciate it.

- Missing You, by Harlan Coben: Though, as mentioned above, I typically gravitate to women authors, I tried Harlan Coben because I have enjoyed the various Netflix series made from his books. Because those series are all set in in the UK, I assumed Coben was British. But not only was he (like me) born in New Jersey, but (like my son) was born in Newark. I liked that this one has a female protagonist. Plot revolved around an online dating service. I find Coben quite accessible and will likely read more of his.

- Run Away, by Harlan Coben: The second of my forays into Coben’s prolific output. I found it compelling, although I found the motive of the murderer rather preposterous. Subject matter here focused on the genetic genealogy, a true-crime area getting increasing attention.

- Win, by Harlen Coben. Win is Coben’s 2021 release (though, who knows, he’s so prolific he could have more releases in 2021). An unusual choice for me – male author, male protagonist, male narrator (Steven Weber, who is really quite a good narrator and excellent at performing a variety of voices). I had the sense this book might be the start of a series about Win, an unapologetic rich guy who is more charming than arrogant. (While viewing a preview of a book in Coben’s Myron Bolitor series, I realized Win was already introduced in that series.) The plot, about the fate of a group of 1970s radicals, didn’t do a lot for me, but I liked the Win character and Coben’s reliable, accessible writing.

- No Second Chance, by Harlan Coben. I chose my 4th Harlan Coben this year because it was on sale. Coben started writing novels in 1990, so this 2003 entry is kind of mid-career. I’d like to think Coben has tightened up his writing and plots since this one, which is very complex and seems to drag in places. Looking back, however, at the 4 previous Cobens I read this year, I’m thinking his best stories are those that have been made into Netflix mini-series. I like his writing and find it very accessible, but haven’t been in love with the plots of any of the novels I’ve read. This one, involving murder and kidnapping, takes place in Coben’s North Jersey stomping grounds. I was amused when the protagonist referred to having been born at Newark’s Beth Israel hospital. I suspect that’s where Coben himself was born, as was my son. I also smiled over early-21st-century artifacts, such as Vioxx, Mapquest, Palm Pilot, banks of phone booths, and beepers. This novel is narrated on audio by Scott Brick, a highly competent narrator whom I encountered often in my earliest audiobook days, especially reading nonfiction. Brick’s pace is relatively slow, which I like for enabling me to pick up plot points, but his pokey reading did add to the draggy quality of the book. Bottom line: I liked the book but found it long and complex.

- Six Years, by Harlan Coben. My 5th Coben novel of this year affirmed that I admire his writing more than his storytelling, although, of the 5, this story from 2013 was the one I liked best. A compelling audio equivalent of a page-turner, Six Years also suffers a bit from a complex and drawn-out plot. For example, I got to what seemed to be a climax that would quickly result in a solution to the book’s mysteries. And then the book continued for another 2.5 hours. The plot: Boy meets girl. Boy loves girl. Girl leaves boy to marry someone else. Or does she? Even though boy witnesses the wedding, evidence emerges that it did not actually take place, and subsequent incidents continue to test boy’s perception of reality. This one was also narrated by Scott Brick.

- In the Deep, by Loreth Anne White: Decent but forgettable thriller about a woman suspected of killing her too-good-to-be-true husband. Canadian and Australian settings.

- Golden Poppies, by Laila Ibrahim. I was delighted to discover a third book in Ibrahim’s series about an enslaved woman and her friendship with the daughter of her master. Golden Poppies takes place well after the Civil War but, of course, still depicts the disparities in how society sees and treats skin color. I’m curious whether Ibrahim will continue the series with the descendants of the original characters.

- The Yellow Wife, by Sadeqa Johnson. Based on a true story, this take on women in slavery tells an uncomfortable tale of the offspring of a master father and enslaved mother who marries a cruel white jailer to protect her child (the jailer agrees to never sell the woman’s son). As the jailer’s wife, she is, at best, a bystander to his cruelty, and at worst, a reluctant participant, even as she plots to get around the evil acts.

- Trail of Broken Wings, by Sejal Badani. Absorbing story of an Indian-American family of daughters and their abusive father. Didn’t catch my interest at first, but was much more compelling as it continued.

- We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves, by Karen Joy Fowler. This novel, about a young woman who grew up till age 5 with a chimpanzee as her “sister,” really read like a memoir, even with its unusual premise. Chimps raised as family members are uncommon, but certainly not unheard of. Fowler’s many references to actual scientific information about chimps and their behavior added to the nonfiction/memoir quality. I found the parts of the book not directly related to the chimp and the protagonist’s relationship with it far less compelling than the chimp parts.

- The Silent Treatment, by Abbie Greaves. This novel gets a big “meh” from me. The husband half of a couple stops speaking to his wife for 6 months. A large chunk of the book has the husband trying to explain to his now-comatose wife why he stopped speaking to her. Except he begins with the early days of their relationship, chapter after chapter tracing its history. Beyond how inexplicable it is that someone would spend that long talking to someone in a coma is the utter illogic of rehashing the entire relationship between husband and wife. In the real world, you would just tell your partner why you stopped speaking. Of course, the relationship rehash is for the “benefit,” or more accurately, torment, of the reader. I wasn’t really enjoying the book, but of course, I wanted to hang on to learn the reason for the silent treatment. Trust me, it wasn’t worth the wait. Reminds me of some of the illogical gimmicks Leanne Moriarty puts in her books to suck the reader in.

- Every Vow You Break, by Peter Swanson. This was my 4th Peter Swanson thriller as I continue my quest for Swanson novels as satisfying as his uber-twisty The Kind Worth Killing. This one involves a woman who, at her bachelorette weekend, sleeps with a man who is not her fiancé and then faces a bizarre and confounding situation on her honeymoon on an island off the Maine coast. This one was as compelling as the other Swansons I’ve read, but, as in at least one other book I’ve read recently (Coben’s Run Away), the nefarious doings that lead to murder and mayhem and the motive behind them just don’t seem very plausible.

- All the Beautiful Lies, by Peter Swanson. If you’d given me this book to read without telling me it was written by Peter Swanson, I doubt I would have guessed he authored it. It’s my fifth Swanson book (of the seven he’s written), but the style does not seem like his. The story involves a young man, his father’s mysterious death, and two enigmatic women who may have been involved in the death. Not until about halfway through the book does anything at all intriguing happen, and even then, it’s not really that intriguing. One tiny clue that links this effort to Swanson’s other works is the author’s ongoing interest in the mystery-book genre, which was the centerpiece of Eight Perfect Murders, Swanson’s 2020 release (All the Beautiful Lies came out in 2018). The mysteriously dead father in All the Beautiful Lies runs a rare-book store, and mysteries are his favorite genre. As in Eight Perfect Murders, several titles and authors in the genre are mentioned. When an author puts out a new thriller just about annually, the quality is bound to vary. While I have not come across a Swanson novel to rival the first one of his I read — The Kind Worth Killing — I’ve found his other books to be pretty good. However, I feel like the author should have left the rather boring and stupid All the Beautiful Lies unwritten.

- 28 Summers, by Elin Hilderbrand. This is the second fairly light “beach read” of Hildebrand’s I’ve read (an Amazon publication even describes Hilderbrand as “Queen of the Beach Reads”). The premise is a “same-time next year” affair that lasts 28 summers. Unlike in the movie Same-Time Next Year, in which both paramours are married, only the man is in this tale, and he comes off as rather a cad because of his divided commitments. The book also exists in a disconcerting parallel universe because the guy’s wife is running for president of the US in 2020, and there’s no pandemic. The reader might be more inclined to suspend disbelief if the author didn’t open every chapter with “what we were talking about” in each of the years in the story, those talked-about items being actual news and pop-culture aspects of THIS universe. I might not have chosen this book had it not been free with my Audible subscription. Still, it’s reasonably enjoyable with a likable female protagonist and a few decent twists. Any book that I think about when I’m not reading it has merit. Hilderbrand structures the book so that we know a big part of the ending in the first chapter.

- The Plot, by Jean Hanff Korelitz. Korelitz’s Admission was one of my favorite books of the year I read it. I read one other book of hers that was so forgettable that I remember nothing about it except it was inferior to Admission. The Plot offered moral shades of gray that made me think, a phenomenon I greatly appreciate in books. For me, the question was not guessing the twist but waiting to see if I was right about the twist I guessed very early (I was). It’s still a pretty decent twist. Many readers will probably find the ending quite satisfying and appropriate; I kinda wish it had gone a different way. Writing this review almost at mid-year, I’d say this was one of the better books I’ve read in 2021.

- Shadow Princess, by Indu Sundaresan. Among the several books I’ve read about women of India and Indian-American women, “historical fiction” has been limited to the 20th century. Shadow Princess was my first foray into an older vintage, in this case the 17th century, specifically the time of the building of the Taj Mahal (1632–53; the book goes about 15 years beyond that). From the small amount of research I did, the novel seems to accurately reflect history, though the author may have manufactured a romance and illegitimate son for the protagonist, Princess Jahanara, daughter of Shah Jahan and Mumtaz Mahal, for whom Shah Jahan had the Taj Mahal built after her death in childbirth. I enjoyed learning the history and culture of that time, but it wasn’t my favorite in the women-of-India genre.

- The Age of Innocence, by Edith Wharton. I try to take an annual dip into 19th-century literary classics. This one didn’t go quite back to the 19th century, having been published in 1920. With this book, Wharton became the first woman to win a Pulitzer Prize for literature. Wharton is a wonderful writer, with great turns of phrase, such as “….bursting with the belated eloquence of the inarticulate” and another about the “tepid honeymoon” a marriage had devolved into. The story, about forbidden extramarital love, felt a bit too familiar to me.

- The House of Mirth, by Edith Wharton. My 2nd foray into “19th century” literary classics this year (this one is closer to 19th, having been published in 1905, and it’s also set in late 19th century) and my 2nd Wharton novel of the year. I was assigned to read The House of Mirth in college for a class called “Woman as Protagonist.” I remember struggling to read it, not because it was difficult, but because I am a pathologically slow reader, which is also the biggest reason I mostly consume books on audio. Something like 5 books were assigned for that class (another that I remember was Kate Chopin’s The Awakening), and I began to wonder whether I could succeed in college with its hefty reading requirements (I could never have been a literature major). I’m pretty sure I read as much of The House of Mirth as I could but then skipped to the ending, which is the only part of the book I remembered. As with The Age of Innocence, I enjoyed Wharton’s writing and turns of phrase. But I didn’t find protagonist Lily Bart all that likable. While she is always gracious and speaks eloquently, she seems to keep making terrible blunders with her life of looming spinsterhood and financial woe. These mistakes seem to spring from the hubris of having enjoyed a privileged upbringing – and just simple stupidity. Scholars have said the central theme of The House of Mirth is essentially the struggle between who we are and what society tells us we should be, and I would add to that the much more stringent requirements that society sets for women and the difficulty of meeting those requirements. The penultimate chapter is poignantly and beautifully written and almost makes up for the slog through Lily Bart’s bad decisions.

- Project Hail Mary, by Andy Weir. Like many, I loved Weir’s The Martian (both book and movie). I didn’t like his followup, Artemis, about space crime, but Project Hail Mary will likely please other fans of The Martian as much as it did me. It offers plenty for both space geeks and science geeks, along with a compelling and suspenseful story. Protagonist is likable and voiced on audio by excellent narrator Ray Porter, who sounds like a cross between Tom Hanks and Jeff Daniels. Delivers a profound message about interplanetary friendship.

- Malibu Rising, by Taylor Jenkins Reid. Reid is one of my favorite authors, and I’ve read and enjoyed most of her books. Occasionally, she writes a gimmicky novel; one of the few I haven’t read involves parallel universes. Malibu Rising is gimmicky in that, while the first half is mostly flashbacks in the life of a family, the second half takes place entirely over the space of 24 hours at a wild celebrity-packed party. Reid also introduces about a zillion characters, most of them party guests. I concluded that all these characters were filler, really not integral to the story. That story, about the children of a famous Sinatra-esque singer, who all achieve varying levels of celebrity themselves despite their father’s neglect and their mother’s death, is worthwhile.

- The Impossible Girl, by Lydia Kang. This novel ticks two of my happy-reader boxes: historical fiction and a highly unusual storyline. It introduced me to 19th-century “Resurrectionists,” criminals who steal corpses, mostly to sell for medical dissection, but also to Barnum-like museum owners who seek freakish corpses. A potentially freakish corpse is our protagonist, Cora, who is born with 2 hearts, and is herself a Resurrectionist. Bonus: She also spent her first 14 years disguised as a boy to help hide her identity from these freak-show types. As the story opens, she now spends part of her time as her female self and the other part as her own twin brother, Jacob. I learned a lot, enjoyed the story, and believe this novel would make a really good movie. In going through my previous book lists, I realized I’d read another of Kang’s books, A Beautiful Poison, but I don’t recall much about it; may have been about opium or morphine. In fact, my 2018 list noted that this book was so unmemorable, I had nothing to say about it!

- A Distant Heart, by Sonali Dev. While this novel is set in a very contemporary India, it’s really not in the genre of “women of India” books I so enjoy. I would describe it as “crime thriller/romance.” As in almost all novels I’ve read about India, class issues take a prominent role, but this one lacked the cultural richness of other books set in India I’ve read. The story didn’t do a lot for me; a rich young woman lives in isolation because of a rare disease and is befriended by a young man far below her social class. The crime-thriller portion centers around an illegal body-parts-for-transplant operation. Not one of the better books I read this year.

- The Sister, by Louise Jensen. Run-of-the-mill improbable thriller in which a young, single woman is too trusting and naive.

- Unfaithful, by Natalie Barelli. I was thoroughly drawn into this thriller set in a college math department. The plot had a lot going on – sexual harassment, infidelity, murder, theft of intellectual property, bad parenting. I thought I had guessed the twist but hadn’t, which made it more rewarding. It was interesting to read this one right after The House of Mirth, because, like Lily Bart, the protagonist of Unfaithful makes a number of bad choices. (I later read in reviews of other Barelli novels that women making dumb choices seems to be a consistent theme.) My only quibble with the book was that some of her reactions to her dilemmas seemed off-base. I thought this was the first Natalie Barelli novel I’d read, but it turns out I also read last year’s The Housekeeper, a book I liked reasonably well but found the narrator of the audiobook badly miscast.

- Missing Molly, by Natalie Barelli. Unbeknownst to me when I was reading this thriller, I was completing the set of Barelli’s 3 latest novels, one of which (Unfaithful), I also read this year. Missing Molly was nothing like Unfaithful beyond being about a young woman in jeopardy. Given that Unfaithful was set in the US (as was the 3rd Barelli book I’ve read) and Missing Molly in the UK, I wondered about Barelli’s background – American or British? Neither; she’s Australian. The premise for Missing Molly was promising: Young woman gets involved in a podcast at work about a pre-teen girl who went missing a dozen years ago after her entire family was murdered. Of course, our protagonist turns out to be the now-grownup missing girl. Unfolds fairly predictably, though, and has the annoying quality of too many books I’ve read recently in which women are ridiculously naive and trusting.

- Band of Sisters, by Lauren Willig. This work of historical fiction tells the interesting story of the efforts of the Smith College Relief Unit in World War I. I use “story” loosely as the flaw of the book is not much story. The young women face a series of obstacles along the way, as well as some romance, but there’s really not enough plot to sink one’s teeth into. The book imparts interesting and previously unknown history, though. I had read two previous historical novels of which author Willig is a co-author. Both had better stories than this one, so perhaps narrative prowess is not what Willig brings to her collaborations (though she seems to quite a prolific author). Perhaps character development is more her strength; I saw that development, along with some compelling statements about friendship. I did get a bit more drawn into the book and characters as the novel progressed, but it just wasn’t narratively strong.

- Find Us, by Benjamin Stevenson. I liked this very short (4 hours on audio) thriller, which had a couple of good twists. Several of the books I read around the same period would have been better if not so long. Find Us proves you can write a satisfying thriller that doesn’t drag on and on. FBI consultant works the case when her own children go missing.

- Amy Snow, by Tracy Rees. I was completely engaged in this Brit historical novel, set in the mid-19th century. The intricate and intriguing plot features a young woman who is found in the snow as a newborn by the daughter of a wealthy landowner. They grow up as sisters, after which tragedy strikes, and the now-grown orphan is set off on a mysterious quest concerning the “sister” who saved her. One of my favorites of the year, slightly marred only by an odd choice on the author’s part to foreshadow the ending in a way that made it a bit anticlimactic.

- The Rose Garden, by Tracy Rees. I enjoyed Amy Snow so much that I welcomed the opportunity to read another piece of historical fiction from the author. Although this one took a little longer than Rees’s Amy Snow to pull me in, I found its story just about as engrossing. It follows the storylines of 3 young women, and of course, these stories eventually converge. (An aside: A trend I’ve noticed in multiple-storyline novels is that some storylines are told in first-person, while others in third. In The Rose Garden, 2 were in first person, the third in third-person.) All 3 stories deal with the role of 19th-century women in society and prevailing myths about women’s mental health. I found the title a bit odd, despite a slight explanation toward the end, as the rose garden made only a couple of brief appearances in the book.

- Who Is Maud Dixon? By Alexandra Andrews. The plot and/or theme of this novel is reminiscent of an earlier read from this year, The Plot, addressing the question of whether anyone has the right to tell another’s story, especially when the story’s owner is no longer living. Theft of intellectual property leaves several bodies in its wake in Who Is Maud Dixon? As in The Plot, righteousness does not exactly triumph in the end. Although the story’s major twist was fairly predictable, I was engaged.

- Dancing at the Rascal Fair, by Ivan Doig. I read several books by the late Ivan Doig back in book-club days in my early years in Kettle Falls. Not sure why I stopped since I enjoyed them; perhaps I thought I had read his full oeuvre, though I had read just 4. I doubt I ever would have started a Doig book had it not been for book club. His books are typically set on the Western frontier. They depict frontier adventures in a fairly lightweight and often comedic style, although this one seems a bit heavier and more serious than the others I’ve read. Dancing at the Rascal Fair was Doig’s third novel; perhaps he got lighter as he went along. His books’ narrators are typically very folksy with a Western twang, and they add a lot to the stories. The narrator of Dancing at the Rascal Fair, however, speaks with a Scottish accent because the novel begins with two young Scotsmen emigrating from Scotland to Montana in the late 19th century. Part of me is fascinated by the struggle of homesteader life on the frontier, but another part feels weighed down by all the hardship. That’s how I felt till I got to the romance at the core of story, which was quite poignant; it drew me in. This novel seemed to have more ribaldry and sexuality than I recalled from Doig’s other books (a surprise, but not an issue). Doig touches on the 1910 fires in the West, which I read about in Tim Egan’s The Big Burn, as well as the effort to establish national parks in the west. This wasn’t my favorite Doig, but he was a wonderful writer.

- Say Goodbye for Now, by Catherine Ryan Hyde. The 3 books I’ve read by Hyde suggest that she focuses on loners, curmudgeons, children, and animals. I like her old-school writing style and the fact that her focus seems to result in storylines that are not same-old same-old. This was another enjoyable, heartwarming read from Hyde, set in the late 50s and early 60s and featuring racial conflict and child abuse.

- The Red Book, by Deborah Copaken Kogan. I’ve often been drawn to novels with this type of storyline – a group of people (usually women) who met earlier in life, usually in a school situation, reuniting much later in life (say, at a reunion or funeral, as in The Big Chill) and holding all kinds of lies and secrets about the intervening years. In this case, it’s members of the Harvard Class of 1989, reuniting during the early Obama years. I wasn’t terribly absorbed in the book, which had way too many characters.

- Night Music, by Jo Jo Moyes. I was a bit trepidatious about this selection. I’ve read 6 of Moyes’s books, and the one I liked the least was one of her earlier works, the same category Night Music, recently published in the US for the first time (first published in the UK in 2008), falls into. While Night Music is different from her later works, I didn’t dislike it. The protagonist is a concert violinist whose husband has died, leaving her and her children in financial straits. This year’s mini-theme of naive and too-trusting women emerges. Much of the story revolves around the dilapidated house the violinist has inherited; thus, I appreciated the atypical subject matter. Not Moyes’s best, but readable.

- Ship of Brides, by Jo Jo Moyes. Another “older” Jo Jo Moyes, this one published in the same year, 2005, as the one I didn’t care for (Peacock Emporium). Ship of Brides is one of Moyes’s forays into historical fiction (e.g., The Giver of Stars), this one concerning war brides who travel by ship from Australia to England just after the end of Wold War II (1946). It’s based on a real event; the real ship was the Victorious vs. the fictional ship, the Victoria, and, of course, the captain’s name and character were fictionalized. I’m sure Moyes made up all the bride characters and their stories. For most of the book, I wasn’t as engaged as I would have liked to be, but I enjoyed it more toward the end. Moyes seems to have a different style for her historical novels.

- The Great Lover, by Jill Dawson. I was not terribly engaged in this cerebral, talky piece of historical fiction. The focus of the book is the poet Rupert Brooke in the early 20th century, and it alternates between chapters in his “voice” and the voice of a housemaid, Nell. As far as I can tell, Nell is fictional (typically authors of historical fiction clarify in an author’s note what’s real and what’s not, but that was not the case here). In The Great Lover, Brooke and Nell have a flirtation bordering on romance. She is his confidante. But much of the book consists of ruminations by both characters, especially Brooke, who struggles with his sexuality, rather than much of any story (according to that flawed source Wikipedia, “Brooke suffered a severe emotional crisis in 1912, caused by sexual confusion [he was bisexual].”) He was rumored to have fathered a child with a Tahitian woman, material also covered in the novel. I was not familiar with Brooke, other than to recognize his name, and I’m not a big poetry fan, factors that probably also affected my lack of engagement. “The Great Lover” is also the title of one of his poems.

- Lady Audley’s Secret, by Mary Elizabeth Brandon. By the time I got to this novel, I was thinking I had read an awful lot of British stuff this year. British works typically comprise a good chunk of my list; it would be interesting to see if I read more than usual this year. The biggest surprise about this book is that it was written in 1862; it truly reads as though it could have been written today. Its Audible description notes that it was “a founding text of the sensation novel genre.” Given the time and genre, I was reminded of Louisa May Alcott’s “gothic thrillers.” This book engaged me. The predictable secret emerged with 6 hours remaining in the book, with the consequences of this secret unfolding through the rest of the book. It was a good and satisfying story.

- A Modern Mephistopheles, by Louisa May Alcott. Alcott is one of my favorite authors, and I’ve long yearned to read more of her works for adults, but very few of them are available on audio. Having thought of Alcott while reading Lady Audley’s Secret, above, I had a yen to read the one adult Alcott I had in my Audible library. This one reminded me of The Great Lover, above, in that it was almost entirely presented as dialogue and inner thoughts. As I’ve said of several books on this list, it wasn’t a favorite among books by this author, but well-written.

- The Crime Writer, but Gregg Hurwitz. I was intrigued by this novel’s premise: Crime author has amnesia covering the period in which his ex-fiancée is killed, with evidence pointing to the author. I was much less intrigued by his draggy efforts to clear his name. I didn’t feel too bad about not paying as much attention as I could have to the draggy parts because I wouldn’t have guessed the killer. The book comes with an interview with the author, which is always fun. Apparently, he considered this novel a departure from his 7 earlier works — first to be written in first person and more character-driven than his previous stuff. I enjoyed Scott Brick’s narration of the novel.

- Great Circle, by Maggie Shipstead. This piece of historical fiction was recommended by Lori Cates Hand, who edited one of my own books. The novel follows the dual-storyline formula in which one character’s story takes place significantly in the past, while the other character’s tale unspools closer to present day. A connection is revealed between the two storylines. The characters are almost always women; in fact, I can’t recall a book I’ve read in this genre with a man as protagonist for either storyline. As I’ve noted about at least one other book on this list, it’s not uncommon for one storyline to be told in third person, while the other is in first person, which is the case in Great Circle. The author also switches back and forth between past and present tense; I could find no discernible pattern to her tense usage. It’s also not uncommon for me to be more engrossed in one storyline than the other; I was more engaged in the story from the past. The past protagonist is an aviatrix in the era of Earhart and Lindbergh. The premise surrounding the modern-day character is clever, a different take on this part of the dual-story equation. The modern character, instead of, say, being related to the past character or stumbling across letters or artifacts belonging to her, this one, actress Hadley, has been hired to play the aviatrix, Marian, in a biopic. Both storylines involve quite a lot of background and build-up, with the reader wondering to what extent all these details will turn out to be relevant and connected, and what meaning will be revealed about the connection between Hadley and Marian. The typical formula has the present-day character making a discovery about the past character; in The Great Circle, the revelation appears only at the very end. All in all, Shipstead is an excellent storyteller unspooling an absorbing saga. Thumbs up from me.

- The Wrong Family, by Tarryn Fisher. This novel was touted as a “taut thriller,” full of twists. I did not find “taut thriller” to be the case until the final quarter of the book, and I did not find the twists especially twisty. It’s the story of a homeless, dying woman (my age, as it happens) who becomes fascinated by a family, and then unbeknownst to them, moves into a vacant apartment attached to their Seattle house and spies on them. She learns a secret and decides to right the wrong she believes the secret represents; thus ensues the taut thriller portion. About the secret: It reminded me of a truly annoying device that author Liane Moriarty used in Truly, Madly, Guilty, in which she spent much of the book referencing “what happened at barbecue,” while implausibly failing to reveal what indeed happened until many chapters into the book. Similarly, in The Wrong Family, the author repeatedly refers to “the terrible thing [name of primary character] did,” of course not revealing what the terrible thing was. It’s just not realistic. If someone in real life were telling stories like those represented in these novels, they would reveal right away “what happened at the barbecue” and “the terrible thing [name of primary character] did.” It’s just a dumb literary device designed to keep the reader in suspense. Lack of likable characters also diminished my regard for the book. In addition, the ending is not especially satisfying. So, I didn’t love this book; it was OK.

- A Perfect Stranger, by Shalini Boland. Populated with unlikeable characters, this thriller had not revealed where it was going more than halfway in. And so it went until the final preposterous chapters unfolded, revealing a decent twist. A second quite unnecessary twist was of the same nature as the annoying device referred to above in The Wrong Family: One of the major characters, who made fleeting references earlier in in the book to “the terrible thing I did,” revealed that implausible terrible thing. Glad this book was included in my subscription and not one I explicitly paid for.

- Stolen Marriage, by Diane Chamberlain. I would characterize this novel as “historical fiction lite” in that it was set during World War II, but historical events were not the centerpiece of the story. The polio outbreak at that time was more significant to the plot than the war was, and the rapidly built North Carolina polio hospital in the book was a real part of history. Still, the mores of the times were significant in the way the protagonist – a young woman who finds herself paying dearly for a terrible mistake she made – is treated by other characters. While this bad treatment makes for an uncomfortable read, and the character’s own “of the times” views regarding the social construct of race and interracial marriage are unpleasant, I found myself looking forward to my periods of listening to the book. I could also tell I was emotionally involved in the book because it kept me awake at bedtime instead of lulling me to sleep (I often set a sleep timer and listen to a book to get to sleep). I don’t necessarily expect historical fiction to be twisty, but this one had a couple of very good twists toward the end. Very absorbing book. Glad to see this author has many more books as I’ll be reading more. (And I belatedly discovered I had previously read one of hers, The Silent Sister, which was pretty good.)

- The Archer, by Shruti Swamy. The final novel I read in 2021 checked a couple of my boxes – women of India and dance, in this case Kathak, one of six Indian classical dance forms. I didn’t enjoy the style first part of the book, told in third-person. I would probably describe this style as lyrical, as the book’s description does, but I felt only this first part fell into this category. I liked the book a lot more when it began to unfold in the first-person perspective of Vidya, the protagonist. As always, I learned a lot about Indian culture and women’s place it, and I was inspired to learn more about Kathak, but this was not one of my favorites in this genre. The book is followed by an interesting essay by the author about the writing of the book.

- Passing, by Nella Larsen. The unexpected addition of the 76th book on my list came about because I saw the film of the same name, discovered the book it was based on was on Audible, and that it was included in my subscription, and that it’s narrated by Tessa Thompson, one of the stars of the film. Despite a few smallish differences, the film follows the book closely. The book was published in 1929 but feels remarkably contemporary. It’s wonderfully written and very short.

Nonfiction

- Good Morning, Monster, by Catherine Gildiner: A devastating and fascinating affirmation of the role childhood trauma plays in mental health. Also compelling for its revelations about the therapeutic process. Loved the fact that the author acknowledged her mistakes as a therapist.

- The Feather Thief, by Kirk Wallace Johnson: Fascinating account about the art of Victorian salmon fly-tying (who knew this was a thing?) and the theft of a huge number of birdskins from the British Museum of Natural History.

- Paul McCartney, by Phillip Norman: A satisfying entry in my Beatles education. This one was touted as offering a lot more post-Beatles history on Paul than previous bios, though frankly, post-Beatles is not all that interesting to me. I enjoyed learning more about his marriages and children.

- Savage Appetites, by Rachel Monroe: Monroe takes a unique approach to women’s obsession with true crime by profiling women in the roles of detective, victim, defender, and killer.

- Girl Walks Out of a Bar, by Lisa F. Smith: One of my periodic dips into sobriety stories (and one of 2 this year).

- The Black Church, by Henry Louis Gates: Read and enjoyed this companion book to the PBS series but found myself frustrated because the book covers more recent history of the black church, while the series ends around the civil-rights movement. I wanted the series to also cover the more recent years.

- Old in Art School, by Nell Painter. I acquired this book because I loved the author’s brilliant History of White People and because it was included in my Audible subscription at no extra cost. Although I myself went to grad school in my 50s, I didn’t find the “old in art school” premise all that compelling. But I enjoyed learning of commonalities with Painter – she lived in North Jersey, as I did at one time. She completed her undergrad art degree on the New Brunswick campus of Rutgers, which I also attended. And she was highly influenced by my all-time favorite artist, Alice Neel (who also makes an appearance in book No. 20 on this list). This memoir was a pleasant enough diversion and offered some important ruminations on not only being old in art school, but also being black, female – AND from New Jersey. Painter makes a good case for my birth state as the victim of scorn and discrimination, and in my experience, she’s not wrong! We New Jerseyans “don’t get no respect.” Narrated on audio by the author.

- The Nurses, by Alexandra Robbins. This very journalistic and well-researched book describes the world of today’s nurses. I got interested in nurses after teaching leadership to members of that profession for a few years. Having done so, I was aware of much of the plight Robbins describes. The author added much detail to my knowledge and also made the book engaging by following the stories of several nurses. Robbins does a good job with her own narration of the book, not always the case with author-narrated books.

- We Keep the Dead Close, by Becky Cooper. This is the story of the author’s 10-year obsession with solving the 1969 murder of a Harvard graduate student. Cooper’s intricate and detailed investigative work drew me in. Particular details of the crime provoked numerous lurid motives, one of which, later disproven, was that the victim had had an affair with one of her professors, who killed her to keep from going public. The book’s subtext is the vicious, toxic, misogynistic organizational culture at Harvard, which reminded me that academia indeed comprises the most vicious and toxic culture I’ve ever been part of. This is yet another author-narrated book on audio. Narration is good, not stellar.

- Ninth Street Women, by Mary Gabriel. This huge, sprawling (39 hours on audio) history of 5 women – Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning, Grace Hartigan, Joan Mitchell, and Helen Frankenthaler – who were part of the New York School of abstract expressionism in the period of the 1940s to early 1960s – was included in my Audible subscription, and I started listening to it as a fill-in between receiving my monthly Audible credits. Fill-in books are those I read when I’d prefer to be reading other titles, usually reading a bit at a time and returning to them when I’m in a similar Audible-creditless situation. As it happened, this book was just the right length between credits. Gabriel writes well and researches even better. I learned quite a lot, not only about the artists profiled, but also about general history (not just art history) of the era, and the men, often artists themselves, attached to the women, for example, Krasner’s husband Jackson Pollack, and de Kooning’s spouse Willem de Kooning. The switch from artist to artist was a bit hard to pick up on audio, and I’m sure I missed a lot just based on the sheer massiveness of the book, but this was a satisfying read.

- The Disneyland Story, by Sam Gennaway. Kind of an embarrassing selection, but it falls into the Disney-bio bucket of my reading and pop-culture interests. Much of the actual construction of Disneyland took place the year I was born; the public announcement of its launch came less than a week after my birth. Growing up on the East Coast, I saw Disneyland as kind of an impossible dream. The notion that I could ever visit a Disney theme park did not become real until Walt Disney World opened in Florida in 1971 (I have still never been to Disneyland and today find the notion of theme parks stressful). The messages that come across in this history emphasize the constant innovation and experimentation that Disneyland has undergone, and how often the innovation had to wait for technology to catch up, or the innovation actually spurred new technology. Walt’s brand of market research was also remarkable; he spent untold hours at the park – even had an apartment there – and waited in lines like any other guest so he could talk to guests and ask their opinions. Revelations about Walt’s personality – such as the fact that he was always coming up with ideas and was extremely micro in his management style – were not new but reinforced by this book. I happened to read this book as the new movie Jungle Cruise was being promoted (you know you have a pop-culture phenom when rides turn into movies) and then serendipitously right afterward, stumbled across a Disney+ documentary series about 6 major attractions at Disneyland; it was fun to recognize some names and facts about them. One oddity: The book is peppered with “Unofficial Tips,” little tidbits of supposedly insider info. I’m troubled by “tips,” which I associate with advice for someone wanting to know how to do something. “Tips” seems like the wrong word for what’s provided here.

- Shattered, by Kathryn Casey. Did you know that the leading cause of death among pregnant women is murder? That’s just one of the things I learned from this highly engaging and well done true-crime epic. I had not heard of the 1999 case of Belinda Temple, who was murdered in her 8th month of pregnancy by her husband, a case influenced by the more famous murder of the also pregnant Laci Peterson. Just exceptionally well researched and reported and the kind of book that’s hard to put down (or whatever the audiobook equivalent is). Because I was unfamiliar with the case, the book was actually suspenseful for me.

- Blood in the Snow, by Tom Henderson. My positive experience with the previous true-crime book, Shattered, made this an easy choice when I saw I already had it in my Audible library. Neither the writing nor the narration were as good as Shattered, but the book was reasonably satisfying for a true-crime junkie.

- Accidental Presidents, by Jared Cohen. As you might guess, this book is about men who became president when the presidents they served under died. I guess taking over when a president (Nixon) resigns doesn’t count, though Cohen touches on that scenario toward the end of the book. In addition to profiling John Tyler, Millard Fillmore, Chester Arthur, Andrew Johnson, Theodore Roosevelt, Calvin Coolidge, Harry Truman, and Lyndon Johnson, the author also sets up the succession story with history of the presidents who died in office. The understory, of course, points to the flaws in presidential succession that have been gradually addressed over 200+ years, culminating in the 25th amendment. In addition to flaws in the process, the author discusses veep selection (more often political than with succession in mind) and preparation – keeping the veep in the loop so he/she is prepared if the worst happens. This was definitely a fill-in book for times I was waiting on another book. Interesting, and definitely gained new learning (e.g., I somehow missed or forgot that Andrew Johnson was drunk at his inauguration with Lincoln), but the book didn’t blow my socks off. Also thought the subtitle was dumb: 8 Men Who Changed History. Don’t all presidents change history?

- If I Can’t Have You … by Gregg Olsen and Rebecca Morris. Gahhhh. Now I’m on a true-crime, uxoricide jag. I was familiar with this case, that of Susan Powell, but had forgotten the horrific outcome. I’ve read two other books by coauthor Gregg Olsen, who writes a lot of true-crime books set in the Pacific Northwest. I was engaged in the story of this truly monstrous crime.

- Twisted, by Mary Pilon and Carla Correa. This Audible Original is framed as a book but comes off as more of a presentation or podcast. I was drawn to it after seeing 2 documentaries in 2021 about disgraced USA Gymnastics doctor Larry Nassar and the hundreds of young girls he sexually abused, which is also the topic of this book.

- Bitter Harvest, by Ann Rule. For a change of pace, it’s not the wife who is the victim in this true-crime story. I’ve read works by the late Ann Rule, but not in a long time. Not sure what accounts for my very long gap in reading the books of this early entrant into the true-crime writing genre. Bitter Harvest concerns the case of Dr. Deborah Green, accused of setting her house on fire, killing 2 of her 3 kids. Also poisoning her husband. Very well researched and reported. One oddity: Rule occasionally threw in irrelevant references to the way things are done in California, contrasting them to practices in Missouri and Kansas, where the story takes place. I wondered if she was from California; she was born in Michigan, spent a lot of time in the Pacific Northwest, especially Seattle, and died in Burien, WA. She did spend time in California researching the Ted Bundy case.

- Every Breath You Take, by Ann Rule. I had a bit of familiarity with the murder case at the center of this, another Ann Rule true-crime volume, because I was at the time living in Florida, where it occurred, but I didn’t know the outcome. The convoluted search for co-conspirators bogs the book down, but it’s not the author’s fault; that’s just how it was. The book’s victim, Sheila Bellush, was the only victim Rule wrote about who specifically requested in life that Rule write about her if she were to be killed. I appreciate Rule’s thorough reporting and compelling writing.

- Stealing the Show, by John Barelli. I learned a few interesting things from this relatively short book on art theft by the former security chief at NYC’s Metropolitan Museum of Art – such as the 3 types of art thieves and how they differ from other thieves, along with conditions that allow or prevent art theft. A third or more of the book isn’t about art theft but other issues that occupy museum security personnel, such as special events, visits by celebrities, and natural disasters (hurricanes, fire). Excellent narration by Mack Sanderson.

- Broad Strokes, by Bridget Quinn. My third foray into women artists consists of profiles of 15 women artists, including my favorite artist, Alice Neel. The author’s cheeky tone and narrator Tavia Gilbert’s energetic and emotive delivery enhance this short book. Quinn integrates her own art-history and creative journey into the lineup of profiles. The audiobook comes with a nice PDF containing images of all the art works discussed in the book.

- Drinking, by Caroline Knapp. I liked this recovery memoir more than the one I read earlier in the year (Girl Walks Out of a Bar, which was a little too light and jokey; it made recovery from alcoholism seem too easy). This one was much more relatable.

- He Wanted the Moon, by Mimi Baird. The majority of this book comprises the journal entries of the author’s father, a medical doctor who suffered from manic depression (far more mania than depression from what I can tell) and was institutionalized in psychiatric (he called them “psychotic”) hospitals. Some of his writing consists of rants about how ineffective the methods and protocols were at these hospitals in treated mental illness.

- English History Made Brief, Irreverent, and Pleasurable, by Lacey Baldwin Smith. I admit that I have long been envious of my cousin Liz, who had a class in British history at the boarding school she attended for high school. I am even more envious that she can recite the list of all English monarchs. True to its title, this volume was indeed brief, hitting primarily on the high points (the author calls them the “memorable points”) of Brit history. I learned a few interesting things, such as that “Norfolk” and “Suffolk” are abbreviations for “North Folk” and “South Folk.” Also intriguing was the author’s account of how, through outdated technology and weak trade policies, England squandered the advantage it gained by pioneering the Industrial Revolution, and then lost any financial advantage through World War I. I also note some gruesome descriptions of torture of royal enemies, as well as cases of “re-executing” and/or torturing people who are already dead. The penultimate chapter takes the reader through the highlights of each monarch’s reign. As for that list of monarchs I always wanted to memorize, the author notes that some monarchs paid a high price to be on that list, citing Lady Jane Grey, who ruled for 9 days and then was executed.

- Inside Scientology, by Janet Reitman (see also sidebar comments at the bottom of this list about a podcast I listened to this year about Scientology). Published in 2011, this book pre-dates most of the explosive exposes of the last dozen years or so of the corrupt organization that is Scientology. It’s also one of the few written by a journalist rather than a former Scientology member. Reitman states from the outset that her intention was to report and write an objective history of Scientology. She certainly produced the most detailed and extensive bio of Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard that I’ve seen. I also learned that current leader David Miscavage grew up in Willingboro, NJ, a town or 2 over from where I grew up – – and was roughly a contemporary (6 years younger than I); I could have seen him at the mall growing up. Reitman deploys an effective structure for the book, choosing to present the early history through the story of an early adherent. Reitman manifests even-handedness by profiling several young Scientologists who hold varying feelings about Scientology; some have lots of positive things to say about the cult, while others express animosity and tell why they left.

- Reclaiming My Decade Lost in Scientology, by Sands Hall. I wasn’t intending to read another Scientology expose, but this one started playing on Audible right after the Reitman book ended, so I said “why not?” This one was a bit different from some of the others I’ve read because Hall always seemed to maintain a healthy skepticism about the cult. She also describes the Scientology classes and auditing sessions she took in the ’80s in much greater detail than I’ve seen elsewhere. Hall was attracted to the learning technology L. Ron Hubbard developed, and she gives a sense of why she and others have found it appealing; she was perhaps also predisposed to accept Scientology because she was on a spiritual quest. Hall did not face the Scientology-imposed barriers to leaving the cult that later ex-Scientologists did; her struggle had more to do with her own spiritual journey. Ultimately, she felt she had wasted the time she spent in Scientology.

- Cold-Blooded, by Carlton Smith. Still more true crime. I wasn’t in love with this one. Providing lots of background in true-crime books is pretty standard, and the background sometimes tells the reader where murder and victim are coming from, but this author seems too go overboard, to the point of giving thumbnail histories of the states the murderer and victim hailed from. He repeated himself frequently. Not that anyone deserves to be murdered, but the murder victim is not especially sympathetic. I also didn’t care for the Audible narrator.

- The Meaning of Mariah Carey, by Mariah Carey. This memoir would seem an odd choice for me. I like Mariah just fine (and love her “All I Want for Christmas Is You”), but I’m no huge fan, and I’m still reeling from the disastrous “American Idol“ season in which she and Nicki Minaj were judges (I blame Nicki for most of the debacle). So, I had 3 reasons for choosing this book: (1) I share a birthday with Mariah; (2) the book was on sale; and (3) I had heard it was good. Whatever my motivations, I’m so glad I did because I found it delightful and engaging, largely thanks to Mariah’s energetic and emotional narration. She falls easily into the top 5 author-narrated memoirs I’ve consumed (including Springsteen, Diane Keaton, and Patti Smith). Given that she begins the book with her declaration that she doesn’t really believe in the concept of time, it’s not surprising that she barely mentions any dates, including our mutual birthday (though she does note she’s an Aires ands cites other diva singers — Aretha, Diana Ross — born within the same week in March that we were). Her story of determination to make it as a singer/songwriter rising from poverty, family dysfunction, and racism is well told. Best of all, audiobook listeners get to hear her sing throughout. Thoroughly enjoyed. I was struck by how much love and respect she seems to have for her fans. I didn’t start the book as a fan, but I ended up as one.

- The 1619 Project, by Nikole Hannah-Jones. Ever since the 1619 Project emerged in 2019, I knew I would eventually consume it in one of its forms — The New York Times Magazine’s special issue in which the project first appeared, the podcast, the curriculum, and now the book, obviously the format I chose. The project is based on the premise that “no aspect of the country that would be formed here has been untouched by the years of slavery that followed [the 1619 arrival of the first enslaved people in what would become the United States].” It’s a must-read addition to my ongoing study of slavery and the social construct of “race.” Like last year’s Caste, The 1619 Project is excruciating and chips further away at my lifelong belief that I was incredibly fortunate to have been born an American. But is is necessary excruciation. EVERYONE, especially our elected representatives, needs to read the chapter on capitalism.

- Scan Artist, by Marcia Biederman. This book is a bit of an oddball choice, but it ticks a couple of my boxes: scams/fraud and kitschy pop culture of the 1950s and 1960s. It’s the story of Evelyn Wood, the speed-reading proponent who launched Evelyn Wood Reading Dynamics, which apparently has been totally discredited (which I didn’t realize). Wood herself was vastly under-qualified to develop an educational program. I was also interested in the book because of my own exceedingly slow reading. I didn’t partake of the Evelyn Wood program, but I did take a speed-reading class in the 1970s. While it introduced a few interesting techniques for getting more out of a book by scanning its contents beforehand, I did not improve my reading speed. In fact, the most important thing I learned was that I really didn’t want to read quickly. Slow reading was an issue with reading assignments in school, and today, I like being able to read more books by consuming them on audio, but I’m at peace with my snail’s-pace reading.

- Caveat Emptor: The Secret Life of an Art Forger, by Ken Perenyi. I was not expecting to like my final nonfiction book of the year as much as I did. It reads a bit like a novel, or at the very least, a memoir that encompasses much more than art forgery. Beginning in the late 1960s, Perenyi, a school-hating guy who used trickery to get out of the draft (and hence, being sent to Vietnam), spins the story of how he got involved in the New York City cultural scenes and ultimately the art world. Perenyi may be under-educated, but he is a prodigious self-didact who learned from experts and museums. He provides copious technical information about forgery, which turns out to be just as much about frames, canvases, shady practices of auction houses, and chemistry as it is about fraudulent painting itself. He truly captures the zeitgeist of the times. Like a novel, the memoir is suspenseful as the reader waits to see if Perenyi will get caught in selling his fakes to auction houses, and we root for him – at least I did – despite his criminality. The narrator, Dan Butler, contributed a great deal to my enjoying the book; I have no idea what Perenyi really sounds like, but Butler’s voice and delivery seem so authentic to the story (despite a few mispronunciations, such as the name of Flemish Renaissance artist Pieter Bruegel).

Podcast Notes: This was not a big podcast year, but I did listen to a few. Notable in relation to my reading more Scientology books has been “Scientology: Fair Game,” hosted by Scientology escapees Leah Remini and Mike Rinder, which takes the opposite tone of the objective, journalistic reporting tone of Inside Scientology. Remini is (very) LOUD and strident. She interrupts constantly to make sure listeners understand her guests’ acronym-rich Scientology jargon. She is passionate in repeatedly expressing her belief that Scientology needs to be shut down, and at the very least, its tax-exempt status revoked. Despite all her flaws, I like Remini; I just have to appreciate anyone who is that passionate and has put so much into a cause she believes in.

I also listened to a podcast about Ghislaine Maxwell that was really more about her late partner Jeffrey Epstein. I caught up on the latest season of Malcolm Gladwell’s “Revisionist History” and enjoyed the first season of “Something Was Wrong” (subsequent seasons didn’t appeal). “Death by Unknown Event,” true crime set in Canada, was another listen, about a woman who seemingly was stalked and assaulted several times. Investigators eventually determined she was assaulting herself, but questions remain.

I listened to all three seasons of “Accused,” from the Cincinnati Enquirer. I liked its commitment to journalistic principles, including the concept that neither reporters nor police should become so invested in a given theory of a crime that they fail to consider other theories. I liked the straightforward delivery by reporter/narrator Amber Hunt. I found it a bit unsatisfying that the unsolved cases remained unsolved, and I missed the interaction and theories from listeners that some podcasts provide.

Finally, at the recommendation of friend Amy Whitehurst, I listened to “Cold,” whose first season covers the Susan Powell case, subject of If I Can’t Have You… on the list above, but covering the case in much greater detail. Very well done. It’s still an absolutely wrenching story.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.